Whole-Exome Sequencing in a Child with Presumed Cerebral Palsy Identifies Aicardi–Goutières Syndrome, a Type I Interferonopathy

From Grand Rounds from HSS: Management of Complex Cases | Volume 14, Issue 3

Case Report

A 9-year-old boy with a presumed diagnosis of spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy (CP) presented with atypical neurologic features and systemic manifestations, prompting reevaluation and eventual diagnosis of a rare autoinflammatory disorder.

The patient was born full term, and was healthy until 6 months of age, when gross motor and language developmental delays emerged. Seizures began at 8 months, followed by progressive spasticity and joint contractures, leading to a CP diagnosis. He was lost to follow-up until age 9 years, when a neurology reevaluation revealed intact hand dexterity, an unusual feature for CP. Review of a prior brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed subcortical white matter dysmyelination without typical CP findings such as periventricular leukomalacia or atrophy. Review of prior laboratory tests revealed intermittent anemia, thrombocytopenia, transaminitis, and elevated inflammatory markers. These atypical features prompted further workup. At age 10 years, whole-exome sequencing identified a homozygous pathogenic variant in the SAMHD1 gene (c.631G>A), diagnostic of Aicardi–Goutières syndrome (AGS) type 5, a type I interferonopathy.

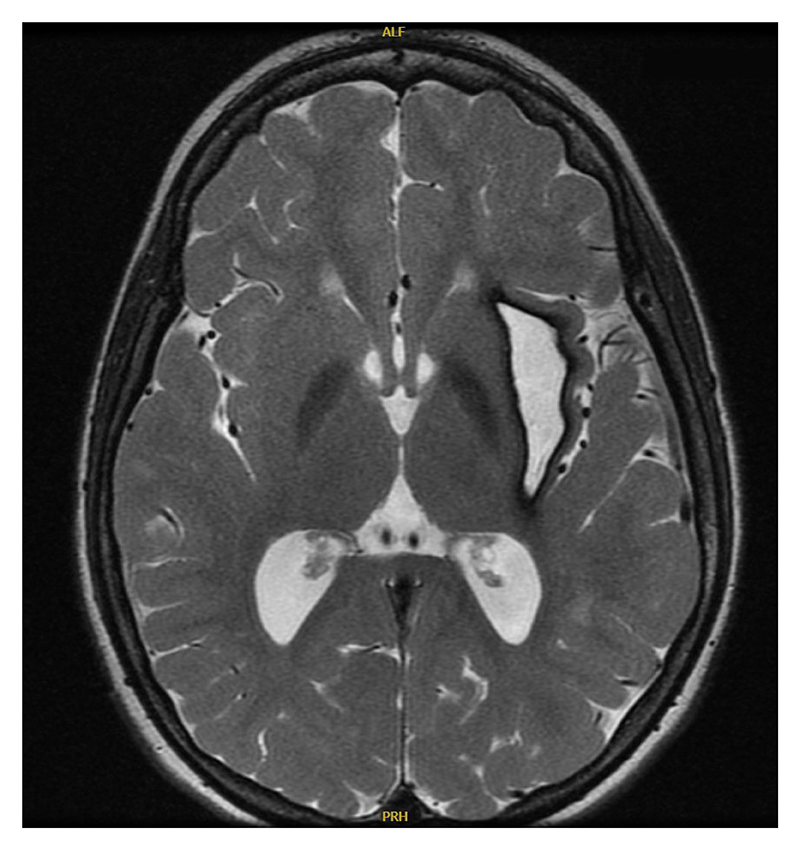

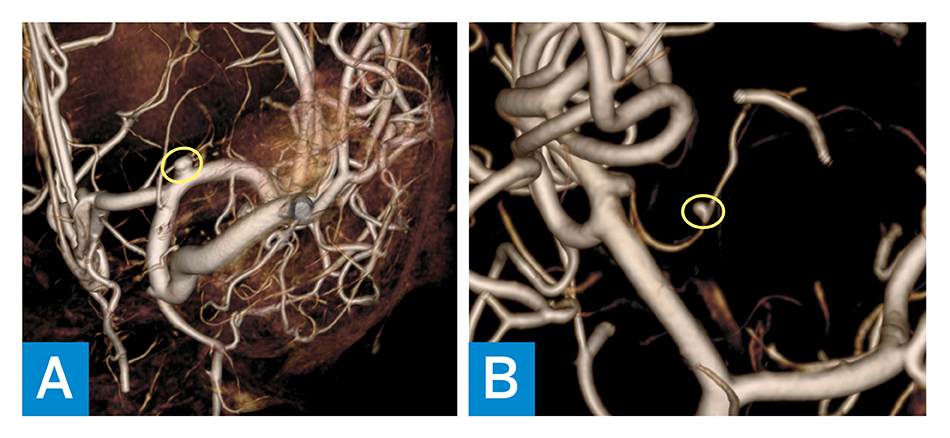

His family history is unremarkable for any autoimmune or autoinflammatory diseases, including interferonopathies. He has older siblings who are healthy. There is no history of parental consanguinity. Additional laboratory workup revealed hypergammaglobulinemia (IgG, 1,960 mg/dL), positive antinuclear antibodies (1:160), and hypothyroidism. Brain MRI and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) showed new T2 hyperintensities, a chronic hemorrhagic cavity in the left subinsular region (Figure 1), and a right medial cerebral artery (MCA) aneurysm. Serial imaging noted aneurysm progression, and angiography at age 14 years revealed persistence of the right MCA aneurysm and a new aneurysm on the left lenticulostriate artery (Figure 2). Endovascular embolization was unsuccessful, and open craniotomy was deferred due to surgical risk. Repeat MRA at age 16 years showed stable aneurysms.

Figure 1: Brain MRI shows T2 hyperintensities and a chronic hemorrhagic cavity in the left subinsular region.

Figure 2: MRA shows the following: A) persistence of the right MCA aneurysm (yellow circle); and B) new aneurysm on the left lenticulostriate artery (yellow circle).

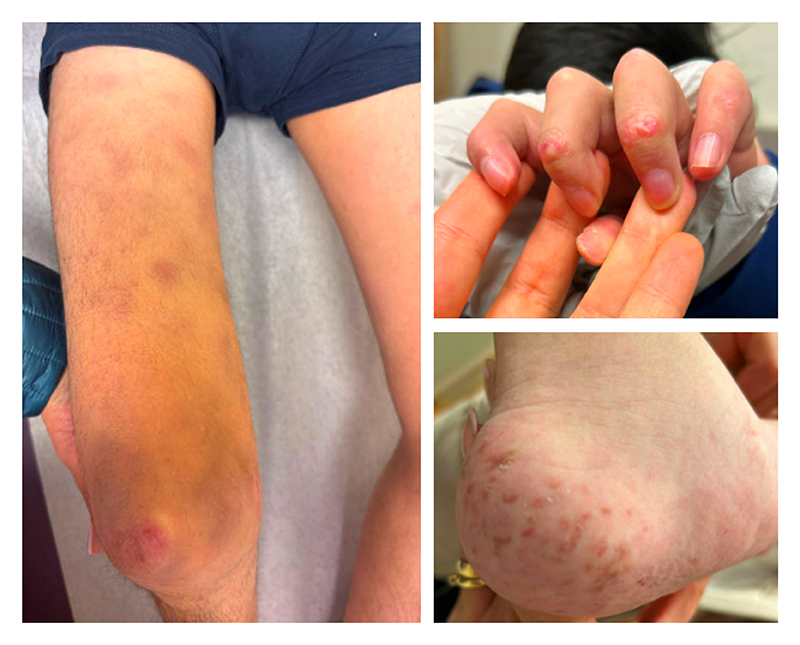

Additionally, he developed chilblains involving the extensor surfaces of several interphalangeal joints, multiple toes, and bilateral heels, which were managed with topical therapies. At age 17, he presented for a rheumatology evaluation, given worsening chilblains and a new nodular rash on the right thigh (Figure 3). Laboratory results showed mild leukopenia (4.8 × 103/µL), elevated C-reactive protein (3.7 mg/dL) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (39 mm/hr), hypergammaglobulinemia (IgG, 2,070 mg/dL), and positive anti-Ro and anti-RNA-polymerase III. Skin biopsy revealed lipophagic panniculitis with positive type-I interferon myxovirus resistance protein A (MxA) staining, consistent with AGS. Therapy with baricitinib and systemic glucocorticoids was started, leading to marked improvement in panniculitis and chilblains within 1 month (Figure 4). At his most recent follow-up 3 months after initiation of baricitinib, he had complete resolution of panniculitis and near resolution of chilblains; however, repeat surveillance neuroimaging revealed enlargement of the right MCA aneurysm compared to previous imaging from 2 years prior, for which he recently underwent a successful pipeline embolization procedure.

Figure 3: Chronic chilblains and a new nodular rash on the right thigh appeared when the patient was 17 years old.

Figure 4: One month after glucocorticoids and baricitinib were started, panniculitis and chilblains were alleviated.

Discussion

Type I interferonopathies represent a group of autoinflammatory disorders caused by monogenic mutations resulting in upregulation of type I interferon (IFN) [1]. The main functions of type I IFN include antiviral and antiproliferation activities [1,2]. As type I IFN may also be elevated in other diseases, whole-exome sequencing is typically required to diagnose an interferonopathy. Despite the varying genetic differences, the type I interferonopathies share common phenotypes involving the skin (such as vasculitis, chilblains, panniculitis), lungs (such as interstitial lung disease), and brain (such as basal ganglia calcifications, neuromotor impairments, epilepsy, and stroke), in addition to recurrent fever and autoimmunity [1].

AGS is a type I interferonopathy associated with gene mutations in SAMHD1, ADAR1, RNASEH2A, RNASEH2B, RNASEH2C, TREX1, IFIH1, LSM11, and RNU7-1, resulting in variable clinical phenotypes of the disease [4]. AGS is predominantly inherited as an autosomal recessive disorder but also has autosomal dominant and sporadic forms [3]. AGS usually presents within the first year of life with severe and progressive encephalopathy associated with abnormal MRI brain findings including intracranial calcifications (especially in the basal ganglia), white matter destruction, and brain atrophy; abnormal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings include CSF lymphocytosis and elevated type I IFN in the absence of infection [2,4]. Our patient’s developmental delay in the first year of his life was initially attributed to CP, but he later developed atypical clinical and radiographic features that prompted re-evaluation of his diagnosis. Ultimately, whole-exome sequencing revealed a SAMHD1 gene mutation, consistent with AGS type 5.

Over one-third of extra-neurologic manifestations seen in AGS are cutaneous, including chilblains, digital vasculitis, skin mottling, panniculitis, lipoatrophy, and psoriasis [3,4]. Our patient had a history of chilblains and biopsy-proven panniculitis. Interestingly, arthropathy with progressive contractures is a unique phenotype found in those with SAMHD1 gene mutations [4]. Other manifestations include intermittent fevers, hepatosplenomegaly, interstitial lung disease, cardiomyopathy, glaucoma, laboratory abnormalities (such as cytopenias, hypergammaglobulinemia, and transaminitis, all present in our patient), hypothyroidism (also seen in our patient), type 1 diabetes mellitus, and other autoimmune features similar to those seen in systemic lupus erythematosus [2,4].

Given the rarity of AGS, no consensus exists on the best treatment approach, although several therapies have shown promise in managing this condition. These include corticosteroids, biologic agents such as anifrolumab, and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs such as Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors [1]. Multiple studies have reported encouraging outcomes from JAK1 inhibition in clinical settings, with baricitinib shown to be especially beneficial for systemic and skin manifestations of various type I interferonopathies [5]. Compared to other JAK inhibitors, baricitinib seems to exhibit a stronger inhibitory effect on signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 1, an important component of the interferon JAK/STAT signaling pathway [6].

This patient was initially diagnosed with CP, which is the most common motor disability of childhood, usually caused by injury to healthy brain tissue [7]. CP results in permanent and nonprogressive disorder of motor function and causes deficits in movement, posture, and balance [8]. The most important risk factor is preterm birth [7,8]. Our patient was born full term with no perinatal complications. Neuroimaging is often abnormal in CP, with periventricular leukomalacia being a classic finding. Our patient had no evidence of periventricular leukomalacia, and additional imaging revealed presence of cerebral artery aneurysms, which are not associated with CP. Additionally, laboratory work-up showed signs of systemic inflammation, not expected in CP.

This case illustrates the diagnostic complexity and evolving phenotype of AGS, emphasizing the importance of reevaluating atypical CP diagnosis in the presence of systemic features.

References

- Haşlak F, Kılıç Könte E, Aslan E, Şahin S, Kasapçopur Ö. Type I interferonopathies in childhood. Balkan Med J. 2023;40(3):165-174. doi: 10.4274/balkanmedj.galenos.2023.2023-4-78.

- Volpi S, Picco P, Caorsi R, Candotti F, Gattorno M. Type I interferonopathies in pediatric rheumatology. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2016;14(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12969-016-0094-4.

- Shwin KW, Lee CR, Goldbach-Mansky R. Dermatologic manifestations of monogenic autoinflammatory diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(1):21-38. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2016.07.005.

- d’Angelo DM, Di Filippo P, Breda L, Chiarelli F. Type I interferonopathies in children: an overview. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:631329. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.631329.

- Crow YJ, Stetson DB. The type I interferonopathies: 10 years on. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22(8):471-483. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00633-9.

- Meesilpavikkai K, Dik WA, Schrijver B, et al. Efficacy of baricitinib in the treatment of chilblains associated with Aicardi-Goutières syndrome, a Type I interferonopathy. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(5):829-831. doi: 10.1002/art.40805. Erratum in: Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(12):2135. doi: 10.1002/art.41564.

- Graham HK, Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, et al. Cerebral palsy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:15082. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.82.

- Vitrikas K, Dalton H, Breish D. Cerebral palsy: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(4):213-220. PMID: 32053326.